We're All Homeless

know what you may be thinking: "Me? No, I'm very sure I'm not homeless." Well if you're having that thought then no, you're probably not homeless in the traditional sense. The We Are All Homeless project has a slightly different message.

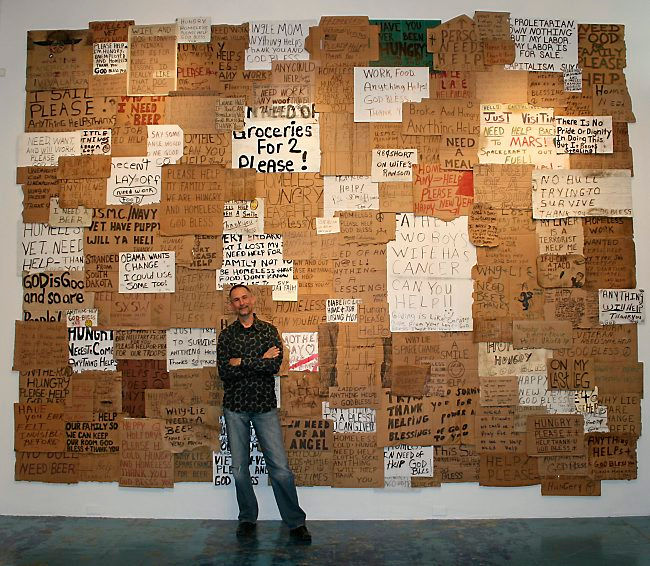

The We Are All Homeless project was started by Willie Baronet, an artist and professor in Dallas, Texas. As many of the themes we've touched on so far would predict, Willie felt uncomfortable when he saw someone experiencing poverty. He felt helpless. He felt like his complacency and moral compass was contributing to homelessness in America.

Willie decided to take a road trip across the country and buy signs from various people experiencing poverty. In doing so, he usually sat down with them, got to know their stories, and began creating art from these homeless signs. In reflecting on his experience, Willie said, "I see these signs as signposts of my own journey, inward and outward, of reconciling my own life with my judgments about those experiencing homelessness."

If you want to watch his inspiring video (only 2:23 minutes!) click here.

I

ver the past 24 years, Willie has bought more than 1300 signs. That's 1300 conversations, 1300 acknowledgments, 1300 steps in a direction that was meaningful for Willie. Is he really sitting here asking us to each buy 1300 signs? Definitely not.

The We Are All Homeless Project beautifully points out that no sign is the same. Every person who experiences poverty is different. Each sign, story, personality, and circumstance is unique. We are all homeless because we all contribute to the different kinds of homelessness, and because of that, it is our responsibility to do something about it.

I already said buying 1300 signs is too much. I'm not asking you to give your life savings to the homeless, nor am I asking you to take every piece of clothing out of your closet and donate it to your local homeless shelter. Let me be clear: I am not asking you to uproot your life to reduce homelessness. Frankly, that would be too much to ask of myself.

Instead, I'm asking you to consider the perspective that we all contribute to homelessness and that every single thing we do in our lives is connected to homelessness.

O

You mean homelessness is all our fault? Of course not, but I think we should examine our lives through this lens of responsibility. To some extent, we are all greedy; we all have selfish desires and wishes, which is understandable. We want the best lives for ourselves and if not for ourselves, then usually for our kids. When it comes down to it, we want to live a happy life, plain and simple. However, it is not only this inherent greed that exacerbates the division between the homeless and the rest of society. It is a matter of helplessness.

Often, people look to the homeless and will make the claim, "Just because these people are homeless doesn't mean they're helpless! Why aren't they doing anything to help themselves?" Well, if we are going to ask that question of the homeless, why don't we ask ourselves? Why aren't we doing anything to help them? We too are responsible.

Another thought on helplessness: the notion that we won't even make an indent if we do indeed decide to help pushes us back into our own lives. The daunting reality that homelessness is growing and will never end, no matter how much we help, can clearly discourage us from getting involved. And yet people don't experience poverty because they have a lower IQ or have less motivation. Homelessness is rooted in helplessness. Homelessness—and the extent to which we allow it to endure—is about all of us.

Still not entirely sure what I mean when I that say every decision, every part of our lives can in some way contribute either cognitively or behaviorally to homelessness? To help clarify, let's return to the beginning of this project, back to where we started.

Just a typical day for us:

ou strut down the familiar, chalky sidewalk smeared with fleeting footprints. It’s a typical night in Chicago, or San Francisco, or Los Angeles, or New York City, or Miami... You see a homeless person, or a homeless family, or an entire homeless community scattered along the partially littered sidewalk, hungry souls waiting like traffic cones on a street... Most likely you don’t say anything at all, not looking their way, not acknowledging their presence on this earth, leaving them to wait for the next human being to toss them their scraps.

You pass the homeless person and continue on with your life. End of interaction, end of your exposure to homelessness. Wrong! You keep walking down the street, confronting your next decision: take an Uber or take public transportation? Take an Uber: you can sit in the back seat of segregation while your driver promptly drops you off at your desired destination. Or, take public transportation: you can witness, contribute, and interact with the diverse faces in your city.

If you take public transportation, you increase your potential time with those experiencing poverty, which may, in fact, have an effect on your cognitive (how you think about homelessness) and behavioral (how you react in response to homelessness) systems. Maybe you have a conversation with someone on the train, maybe you don't. At least you have the opportunity to think and act without a barrier between you and homelessness.

Y

It doesn't stop there. The next morning you decide whether to make coffee, buy coffee, or even drink coffee. If you decide to make coffee instead of buying coffee, or not to drink it all together, where does that extra money go? It's up to you.

How can we reduce income inequality in our day-to-day lives? The socioeconomic gaps are more divisive now than ever before. For instance, income inequality in America, according to the Gini coefficient, a scale in which 0 is perfectly equal and 1 is perfectly unequal, is at 0.45. For some perspective, Iran's is 0.44

If we continue to look at homelessness as something distinctly different in our lives, isolating it as its own problem, what will you think when you walk down the street? Your normal life, normal job, normal clothes, and then you see that sitting on the sidewalk. That cognition—the dehumanization of people experiencing poverty—followed by a lack of behavioral action, is the match that lights the fire. We are not part of the problem; we are the problem.

ere's what we can do. By aligning our cognition with our and behavior, one by one, we can begin to ethically break down the artificial barriers that we've constructed between people who experience poverty and people merely living their lives. If you approach a homeless person, acknowledge them, and treat them like a human being (ethical cognition), and then go home and support that cognition by carving out a weekly time to volunteer with your family over the weekend, or read literature on racial and economic segregation, or set aside a fraction of your income to donate to an organization that speaks to you (ethical behavior), it will make a small difference. One by one, those small difference will start to add up.

If we bring the stigmatic and problematic issue of homelessness into everything we do, cognitively and behaviorally, together we can make a real impact.

Just so it's clear, it's important for me to say that I don't practice this perfectly myself. Throughout this journey we've taken together, I've taken on this responsibility—to try and bring homelessness into everything I do. Again, I do not intend to displace your lives and do not expect you to sign on for a lifetime solely committed to homelessness prevention, but it begins with the awareness that homelessness does not simply occur on the street. It happens in our beliefs, in our behaviors, in our thoughts, and in our decisions.